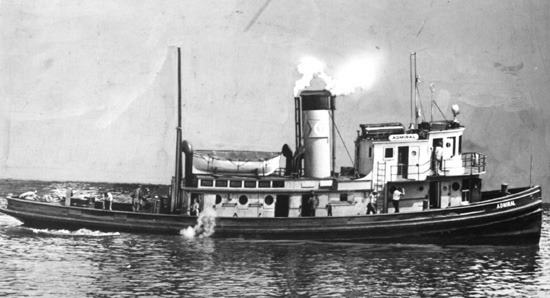

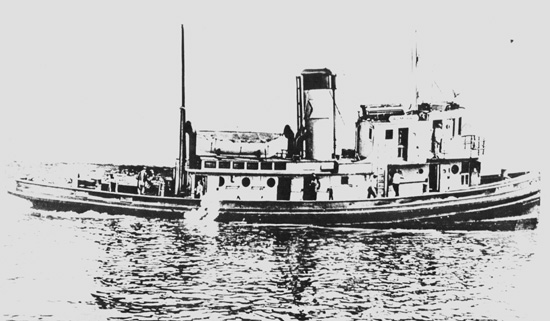

Admiral

| Ship Name: | Admiral |

|---|---|

| Also Known As: | Built as W.H. Meyer, renamed Admiral in 1942 during time of vessel rebuild, only 89 days before her sinking. |

| Type of Ship: | Steel propeller tugboat |

| Ship Size: | 93' x 22' x 11' |

| Ship Owner: | Barge and tug operated at time of sinking by Cleveland Tankers, Inc. Tug owned by Allied Oil Co., Cleveland, Ohio |

| Gross Tonnage: | 130 |

| Net Tonnage: | 88 |

| Typical Cargo: | Tow tug, and occasional harbor icebreaker |

| Year Built: | 1907 - Manitowoc Ship Building Co., Manitowoc, Wisconsin |

| Official Wreck Number: | 222239 |

|---|---|

| Wreck Location: | 41 38.243 N 81 54.198 W (Kohl) Mooring Buoyed by MAST |

| Type of Ship at Loss: | Same, with barge Clevco in tow. The tanker barge Clevco was loaded with fuel oil. |

| Cargo on Ship at Loss: | Towing barge Clevco, the barge Clevco was full of oil. |

| Captain of Ship at Loss: | Barge and tug operated at time of sinking by Cleveland Tankers, Inc. Tug owned by Allied Oil Co., Cleveland, Ohio |

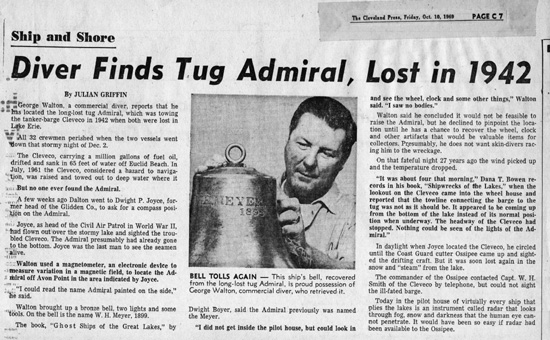

One of six shipwrecks with a mooring buoy placed by MAST. Popular wreck for scuba divers. Initially located in 1969 by Cleveland commercial diver George Walton (Cleveland Press, October 10, 1969). Walton recovered the tug's bell and other artifacts for proof, yet would not give up the shipwreck's location.

Unfortunately, many artifacts have been removed and remain in private collections. Other artifacts, including the ship's bell, can be viewed at the Great Lakes Historical Society in Vermilion, Ohio. This was prior to the Ohio Shipwreck Protection Act of 1991, which made disturbing or taking any shipwreck artifact illegal.

Divers report that, prior to the invasion of the zebra mussel in Lake Erie (1988), the name "Admiral" was clearly visible on the side of the bow. Today, the name has been obscured by zebra mussels, and the entire tug is covered almost beyond recognition by this invasive mussel.

Early divers of the Admiral reported her stern to be visible and sitting above the bottom. Today, however, the stern is almost buried under silt and mud, with the smokestack along the port side in the muddy bottom. Although the pilothouse and engine room are diver accessible, experienced wreck divers caution against penetrating the wreck without prior wreck penetration training and preparedness. (Russ MacNeal, Underwater Dive Center, Elyria, Ohio)

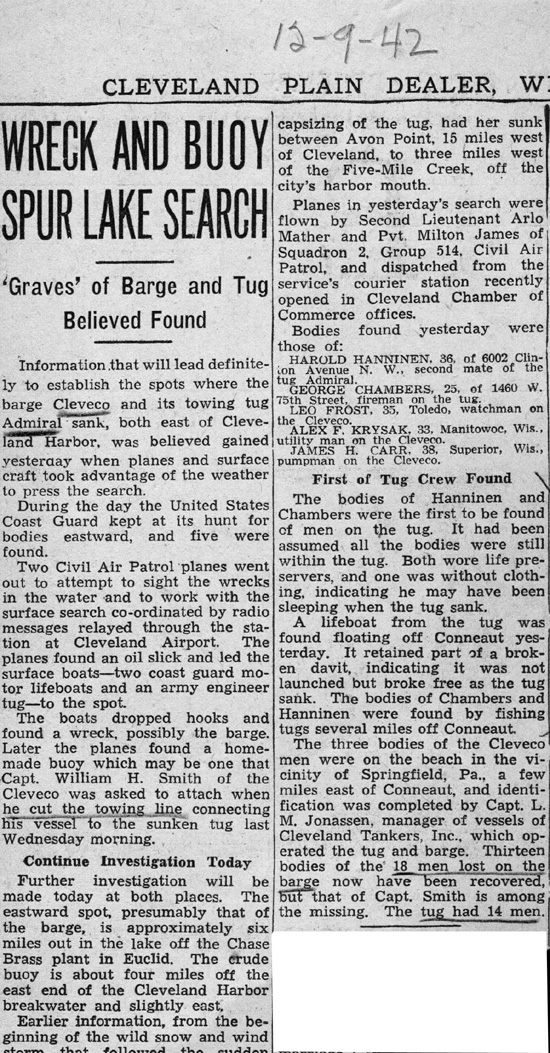

December 2, 1942. Foundered, capsized and sank approximately 10 miles north of Avon Point, Ohio, and 18 miles west/northwest from Cleveland Harbor. Capsized during a fierce winter gale while towing the tanker barge Cleveco, which was loaded with a wartime cargo of fuel oil.

The Cleveco drifted further east, sinking offshore of Euclid, Ohio. Fourteen lives lost on Admiral, eighteen on Cleveco. All bodies from the Cleveco, except for the captain, were recovered. Only three bodies were recovered from the Admiral.

It was reported that both vessels began to accumulate ice buildup prior to sinking. The snow was heavy enough that, although tethered together by the tow line, neither vessel could see each other. At approximately 4 A.M., the captain and crew of the Cleveco noticed their direction of tow with respect to the wind had changed, and the tow line from the Admiral was now going directly down into the depths of Lake Erie.

It is not known if the order was given to severe the hawser (tow line), or if the hawser between the two ships had simply parted. Speculation is that heavy seas, high winds, or possibly even a bad steering gear forced the Cleveco in a sharp starboard direction, with the Admiral going to her port, and both on different wave crests.

Prior to the disaster, however, the Admiral had been inspected by the US Coast Guard after being reconstructed in 1942. The purpose of the inspection being to determine the Admiral's seaworthiness following the rebuild, which oftentimes would change the center of gravity of a vessel. The certificate issued following the USCG inspection indicated her to be seaworthy, with some restrictions, one of which was to maintain the tow as practically as possible in a fore-to-aft line. However, a memorandum to the USCG office in Washington from the inspection officer did state the Admiral was slightly "deficient in stability"; referred to as being "tender" in seaman's language. This situation may have lead to the Admiral's sinking with all hands; especially if the strain on the tow hawser, as speculated above, simply flipped the Admiral over with no time for the crew to escape, let alone ponder their situation.

The following dramatic account of the Admiral/Cleveco sinking was taken from Ships and Men of the Great Lakes, Dwight Boyer, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York 1977. ISBN 0-396-07446-4 chpt. 36, pgs. 313-321:

"Most of the important shipwrecks are of many years ago. Seldom are the steamers of today wrecked. But as late as 1942, Lake Erie claimed the steam tug Admiral and her tanker-barge Cleveco, along with every one of the crew members of both ships, all within the normal range of the lights of Cleveland Harbor. Thirty-two men perished in the wrecks of the two vessels in what is considered the worst marine disaster to overtake lake freight shipping in modern times.

Heroic attempts by many craft to reach the foundering Cleveco during the height of one of Lake Erie's worst snowstorms, and their subsequent failures to locate the drifting barge show conclusively that men will still brave the dangers of storm and cold in the hope of rescuing distressed sailors. Even the help of radio telephone communication aboard the ships figuring in the disaster could not save the unfortunate crewmen.

It was Tuesday afternoon, December 1, 1942, when the big tug Admiral took the towline of the tanker-barge Cleveco in Toledo Harbor, pulled her down the Maumee River to Lake Erie, and squared away for the ninety-six mile run along the south shore of the lake for Cleveland. The tanks of the Cleveco held one million gallons of crude oil. The weather was average for early December, and there was nothing to forecast the doom of the two ships. On through the long night, the Admiral churned her way eastward. The wind began to roll up an occasional breaker against the sides of the tug and her consort, and their force became greater after midnight. The thermometer dropped suddenly. At midnight it stood exactly at the freezing mark and by early morning it registered twenty-four degrees.

It was about four that morning when the lookout on the Cleveco came into the wheel house and reported that the towline connecting the barge to the tug was not as it should be. It appeared to be coming up from the bottom of the lake instead of its normal position when underway. The headway of the Cleveco had stopped. Nothing could be seen of the lights of the Admiral.

Captain William H. Smith of the barge held a consultation with his officers - his brother, Edwin S. Smith, was the first mate. What had happened to their tug Admiral? They decided that she had capsized or foundered and was at that very moment lying on the bottom of Lake Erie, although no one aboard the Cleveco had actually witnessed the accident. It was a tragic moment for the men on the tanker-barge. If their guess was true that the Admiral had sunk, then fourteen of their fellow sailors, who comprised the officers and crew of the tug were in dire straits, or possibly were drowned. Nothing could be heard or seen of them from the Cleveco. Definitely the Cleveco was left without propulsion power. Her own predicament demanded immediate action. The storm was beginning to rise, which added some anxiety to their situation.

Captain Smith, the sixty-two year old skipper, coming from a long line of lake men, turned to his radio telephone and reported his plight to his shore connections. He asked that other tugs be sent to bring in his ship at once.

The captain gave his location then as about fifteen miles off Avon Point, fifteen miles west of Cleveland. He stated that his vessel was in no immediate danger but needed a tug promptly, and that his situation was not good due to the increasing wind and cold. There were ample provisions aboard, and the crew were not suffering, as the donkey boilers were providing ample heat for comfort.

Two husky tugs, the California and the Pennsylvania, of the Great Lakes Towing fleet left Cleveland Harbor to assist the Cleveco, and proceeded toward the spot indicated in Captain Smith's report. What actually happened to the towline between the Admiral and the Cleveco still remains somewhat of a mystery, but it is generally believed that the barge men let go the line and allowed their powerless vessel to drift with the wind toward Cleveland Harbor.

Upon reaching the site, the two tugs were unable to locate any sign of the Cleveco. The storm had increased in intensity in the meantime and was now swirling great masses of snow over the surface of the lake. The severe and sudden cold had caused a fog or steam to form on the surface of the lake which, with the swirling snow, made visibility exceedingly difficult. This condition grew worse as the day went on. The wind also increased during the day. Apparently the Cleveco let go both her anchors after cutting loose from the sunken Admiral. But both anchors were not sufficient to hold the heavily-laden tanker in the gale. She continued to drift eastward and away from the shore line.

Many craft joined in the hunt for the elusive Cleveco, both on the lake and in the air. Some reported spotting her for a short time, only to lose her again in the snow and mists. Telephone communication with the drifting ship was maintained throughout the morning and into mid-afternoon. The searching craft were battered by the terrific seas and high winds and stung by the cold. The Coast Guard sent out all available boats, and the cutter Ossipee joined in the search. The commander of the Ossipee contacted Captain Smith of the Cleveco by telephone, and details of the proposed rescue were discussed.

After a fruitless search of the waters off Avon Point, the rescue craft decided the information was erroneous and requested that Captain Smith give better location of his ship. Her position was then established as ten miles north of the west Cleveland light. Very valuable time and energy had been lost and now the Ossipee carried on the search alone, being the largest vessel in the rescue fleet. Smaller Coast Guard boats were forced to return to shore. The wind howled over the lake at thirty-five miles per hour, and the thermometer hovered around fourteen degrees at noon on Wednesday, the second of December.

About one-thirty that afternoon the officers of the Ossipee managed to get a glimpse of the ill-fated Cleveco, but she was quickly lost to view again. They circled the spot for hours hoping for another sight of her. About two they saw her again for a moment, then she disappeared forever. But contact was maintained between the two ships by radio telephone. At first Captain Smith said that his crew were in no danger and would prefer not to leave their ship. Subsequent messages indicated that the storm was beginning to wreak its vengeance upon the luckless tanker-barge and that the men considered their situation dangerous. Final calls asked that they be taken off the Cleveco. By three-thirty a message was received stating that the tanker was taking water and it was feared this would kill the ship's generators, which would put out the radio telephone and also the entire electrical system of the tanker.

The wind increased to a velocity of sixty miles an hour, with occasional gusts up to seventy. The final message came from the Cleveco at four-forty that afternoon. The Ossipee commander radioed to have the crew of the tanker pump oil onto the water, hoping thereby to calm the surface and possibly make a "slick" which might help locate the Cleveco. No reply came back.

The gallant Coast Guard cutter remained at the scene on wild Lake Erie all that night. The ship took a terrific pounding in the darkness as the storm had intensified into a full gale with waves eighteen to twenty feet high and visibility of zero. The gyro compass went out of order and she was forced to use her stand-by magnetic compass. Her safe was torn loose from its fastenings. Veterans of many years service became seasick. Meals could not be served because of the severe rolling of the cutter. The outside of the Ossipee became coated heavily with ice which eventually effected her maneuverability. It was indeed a tough round of duty for the crew of the cutter.

At last daylight came, and with it the men aboard the battered Ossipee were able to see two bodies floating alongside, which they managed to bring aboard. The bodies were covered with heavy oil and wore life belts from the Cleveco. The Ossipee gave up the vigil at nightfall. Shrouded completely in thick ice, she limped into the harbor of Fairport, Ohio, after thirty-six hours of continuous duty. After clearing the coating of ice, she once more steamed out onto the lake in search of other bodies of the crew of the lost tanker. It is supposed that the Cleveco went down in the darkness of Thursday morning, December third. The tanker had taken the lives of her entire crew, eighteen men. Only an oil "slick" was left on the surface of Lake Erie to mark the spot where she went down. For several days Coast Guard motor lifeboats, the cutter Ossipee, Coast Guard Auxiliary vessels, and other private craft, along with the tanker Comet of the same fleet as the Cleveco, and several planes, continued the search for bodies of the crews of both the Admiral and the Cleveco. Several were found from both ships. Some are believed still to be within the cabin walls of both vessels, trapped there as their ships went down.

It has been scarcely a decade since the Admiral/Cleveco disaster and even in that comparatively short space of time, scientists and marine men have overcome the direct cause of the failure to locate and possibly rescue the Cleveco. Today, in the pilot houses of most of the ships that ply the Great Lakes is an interesting instrument called a radar that looks through fog, snow, darkness, and thick weather, where the human eye cannot penetrate. It can locate another ship, or even smaller objects, such as buoys. It shows the shore line clearly. It does even better in its service to the mariner - it shows exactly how many miles distant is the object of the search. Then it accurately indicates the direction from the searching vessel. It can even look over the horizon! What a Heaven-sent aid to the men who sail the ships today! It was unknown to sailors in the days of the Admiral and the Cleveco. Had the Ossipee been equipped with a radar, locating the Cleveco would have been but a routine matter of looking into a darkened ground-glass screen, similar to a television screen, and then watching a glowing spot inside a series of circles, which would represent the other vessel.

The exact whereabouts of the sunken tug Admiral are still a mystery. The lake bottom has been carefully "swept" in the hope of locating the wrecked hulk of the big tug, but it still defies the efforts of the searchers. Could it be possible that within another decade scientists and mariners working together will develop an instrument with which they can look at and examine the floor of the seas from the deck of a ship? It is even now in an embryonic stage.

Better success was attained in the search for the Cleveco. It still lies where it sank, approximately four and one half miles out in the lake off the resort of Euclid Beach, in some sixty-five feet of water. The hull has been examined by a diver, who reports that the ship is resting bottom-side-up on the floor of the lake. It is thought by many that her cargo of oil might still be intact, provided that her tanks have not been strained to the point of opening at the seams, or connections broken. Salvage men have considered the possibility of raising the Cleveco, but up to the present time the tanker-barge is still where she came to rest after her sinking during that wild gale on Lake Erie in early December of 1942.

The sturdy Coast Guard Cutter Ossipee is no more. The service decided that the old veteran of many a lake gale was obsolete, and ordered her sold. After spending many long months idle in Cuyahoga River at Cleveland, the cutter was finally sold for scrap and was dismantled.

Worst disaster in Lake Erie since the Sand Merchant loss on October 17, 1936.

Claimed to have been located in 1969 by commercial diver George Walton, of Cleveland, Ohio. He retrieved the ship's bell, imprinted "W.H. MEYER", the former name of the tug when built for the Milwaukee Towing Company in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. He refused to give anyone the location. Other divers, however, claim to have dove the wreck during the 1970's on a regular basis.

Divers finally located the wreck again during the spring of 1981 (or finally decided to make the location public) and reported finding human remains aboard the sunken tug. Scuba divers gathered the remains, took them a short distance from the shipwreck, and buried them in the bottom mud and silt of Lake Erie.

On Friday, September 11, 1981, 25 relatives of the Admiral crew were taken to the site of the shipwreck by the US Coat Guard cutter Neah Bay, for a long-awaited memorial service. Their opportunity had finally come to give their loved ones a final blessing. (Elyria Chronicle-Telegram, September 12, 1981)

Great Lakes Historical Society, Peachman Lake Erie Shipwreck Research Center (GLHS/PLESRC), P.O. Box 435, 480 Main Street, Vermilion, Ohio 44089 Historical Files and Photo Collections

Ships and Men of the Great Lakes, Dwight Boyer, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York 1977. ISBN 0-396-07446-4 chpt. 36, pgs. 313-321

The Great Lakes Diving Guide, Cris Kohl 2001, Seawolf Communications, Inc. P.O. Box 66, West Chicago, Illinois

(Russ MacNeal, Underwater Dive Center, Elyria, Ohio)

Cleveland Plain Dealer, 12-3,4,9, 1942

Great Lakes News, December, 1942

Elyria Chronicle Telegram, September 12, 1981, "Admiral Given its Final Salute", Steve Fogarty, C/T Staff Writer