Sand Merchant

| Ship Name: | Sand Merchant |

|---|---|

| Also Known As: | None |

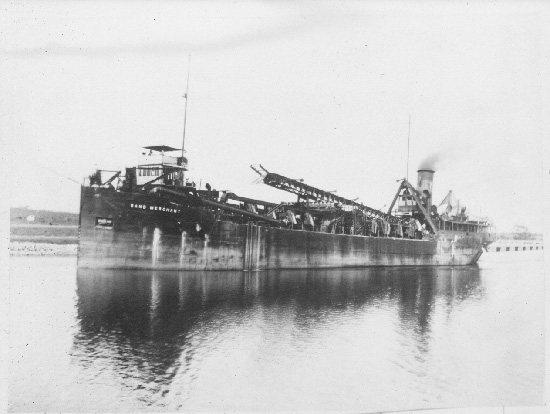

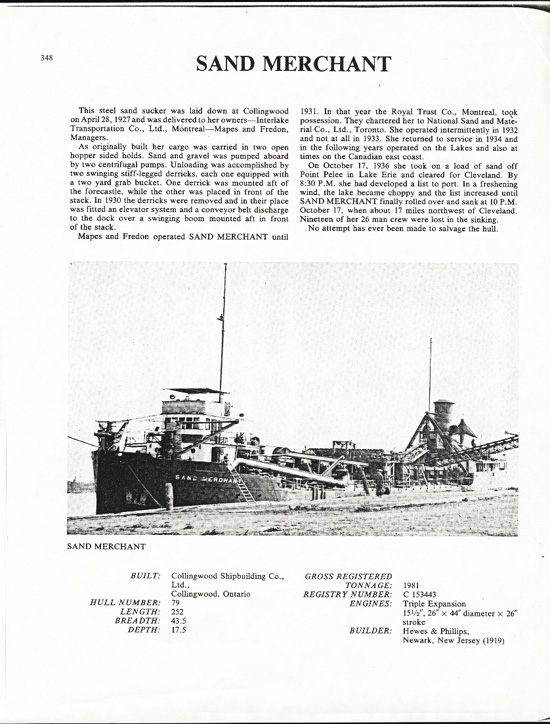

| Type of Ship: | Steel bulk-freight, "sand sucker," steam engine propelled |

| Ship Size: | 252' x 44' x 20' |

| Ship Owner: | First owners, Interlake Transportation Co. Ltd., Montreal, Quebec. 1931, ownership transferred to the Royal Trust Co., Montreal, who chartered her to National Sand and Material Co., Ltd., Toronto, Ontario |

| Gross Tonnage: | 1981 |

| Net Tonnage: | NA |

| Typical Cargo: | Sand, Gravel |

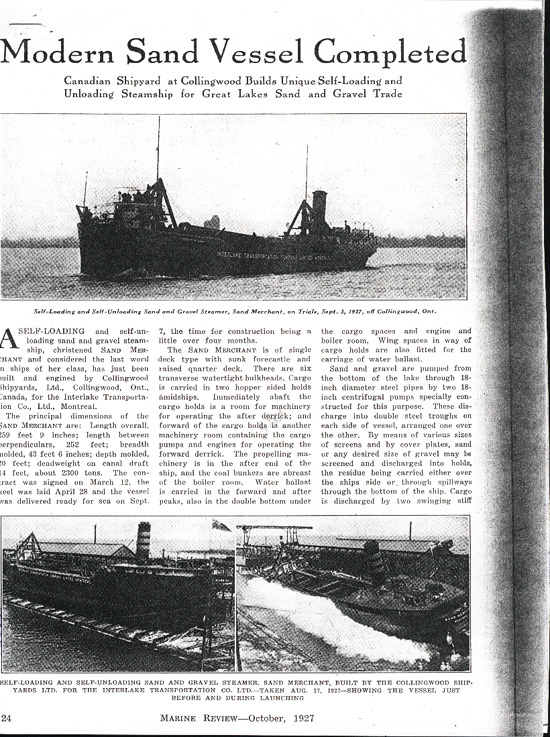

| Year Built: | 1927 - Collinwood Shipyards, Ltd., Collinwood, Ontario, Canada. Designed and built specifically as a sand sucker. |

| Official Wreck Number: | C153443 (Canadian registry) |

|---|---|

| Wreck Location: | 41 34.431 N 81 57.520 W (Kohl) |

| Type of Ship at Loss: | Same as above |

| Cargo on Ship at Loss: | Sand from Point Pelee, Ontario, Lake Erie bound for Cleveland, Ohio |

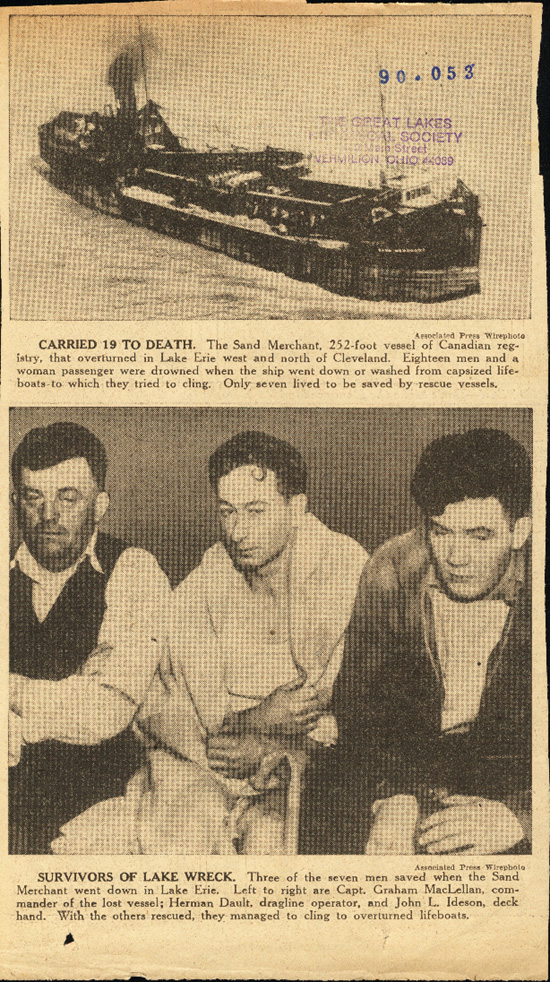

| Captain of Ship at Loss: | Graham MacLelland of Cape Tormentine, New Brunswick (rescued) |

Lies upside down on a mud bottom in approximately 60 feet of water, bow facing southeast. Piles of debris, two deck cranes and other items scattered around wreck. Zebra mussels have covered wreck and all other items. Experienced wreck divers recommended this wreck is unsafe to penetrate.

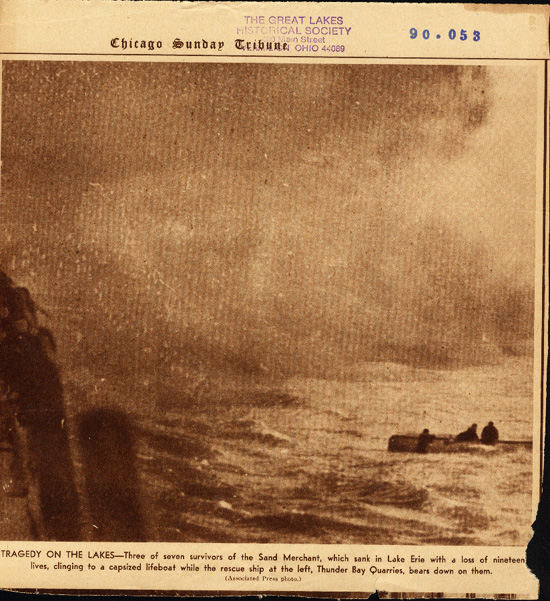

Foundered, October 17, 1936. Approximately 17 miles NW of Cleveland, Ohio in a gale. Loss of life: 18 crew, one passenger.

The Sand Merchant unloaded sand at Windsor, Ontario, on the evening of October 16, then steamed for the sand pumping grounds offshore of Point Pelee, Ontario. At approximately 2:30 AM on October 17, the Sand Merchant began sand sucking her next load, bound for delivery to Cleveland, Ohio, later that day. The prime sand location for sand suckers at that time was off the Canadian shore between Southeast Shoals light and Point Pelee, almost to the western basin of Lake Erie. While in port at Windsor, Lillian Drinkwater, the wife of first mate Bernie Drinkwater, came onboard. Although against ships rules, occasionally the captain would overlook such activity in order to appease a lonely sailor. Unfortunately, this turned out to be a fatal decision for Mrs. Drinkwater. The following very interesting (yet rather long) account of this fateful evening was taken from: Ships and Men of the Great Lakes, Dwight Boyer, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York 1977. ISBN 0-396-07446-4 (pgs. 74-87)

Things were tough in 1936. The Great Depression had seemingly sapped the life from the nation, including the shipping industry. Saltwater ports were crowded with skilled seaman now "on the beach," while at dockside or tethered to mooring buoys in the roadsteads of the world, hundreds of freighters grew scabrous with rust and neglect.

On the Great Lakes many of the long steamers were idle, anchored in clusters in protected waterways or strung out along silent docks, their crews dispersed to join the lines of the unemployed. The few iron ore, coal, and grain carriers that did operate often did so briefly or sporadically. Such were the times that skippers were sailing as wheelsmen, deckhands, and watchmen. Down below, chief engineers worked as second or third engineers, while the former seconds and thirds served as oilers and wipers.

Particularly hard hit were Canada's Maritime Provinces, heavily dependent upon the sea and where jobs, even in good times, were hard to find. From St. John's Corner Brook, and scores of little granite-rimmed Newfoundland harbors, countless hard-working "Newfies" ranged far afield, restlessly combing the coasts and inlets for jobs. So did their seafaring brethren from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Strangely, many found jobs on the Great Lakes, where every port and hiring hall had long lists of qualified but unemployed sailors. One can only suspect that it was because they worked cheaper and demanded less in the way of creature comforts aboard ship.

Nowhere does the jungle telegraph work more effectively than in the world of the sailor. Call it nepotism or what you will, when openings developed or were even rumored, relatives, friends, and neighbors were the first to know and respond. The old adage 'a word to the wise' functioned perfectly. Consequently, the crew lists of many Canadian lake vessels found small, deepwater communities heavily represented by seamen working in a variety of capacities.

A case in point was the sand sucker Sand Merchant the day she steamed westward from Montreal. It chanced to be June 20, 1936. It was really quite a strange affair, although her owners, the National Sand and Materials Company of Toronto, undoubtedly knew what they were doing. The Sand Merchant, after working the coastal trade, was ordered to rendezvous with another company sand sucker, the Charles Dick, Captain Graham McLelland master, at Montreal. Here the Sand Merchant's crew was paid off and the Charles Dick's men transferred to her. The Charles Dick, presumably, would later muster another crew and replace the Sand Merchant in the company's coastal areas of operation. The Sand Merchant would go to the lower lakes, there to bustle about her business of sucking up several grades of sand from the bottom of Lake Erie, delivering it to various ports. She would range about a bit because the sand was used primarily in the construction and building trades, which, like everything else, were vastly depressed.

There was a curious mixture of friends and relatives aboard the Sand Merchant when she departed Montreal. Together they comprised more than half of her crew of twenty-six. Captain McLelland was from Cape Tormentine, New Brunswick, as was fireman Harold Cannon. From the nearby New Brunswick communities of New Castle, Rexton, and Bay du Vin Beach were William Gifford, Roland DeMille, Peter Daigle, John Hebert, and Walter McGinness, the vessel's chief engineer. From Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, came second engineer Martin White and his son, Harry, a deckhand. Other Nova Scotia men were deck engineer Jack Meuse, from Yarmouth, and Nicholas McCarthy, an oiler.

But the largest representation was not from the Maritime Provinces but from Victoria Harbor, Ontario, in the heart of the Georgian Bay country. Second mate Daniel Bourrie must have had influence somewhere, for shipmates were his brother, Wilfred, a wheelsman; Alphonse Robitaille, his brother-in-law from nearby Midland; and the three Dault brothers, Herman, Joseph, and Amos. Also from Victoria Harbor was Sanford Gray, third engineer. Herman Dault was the only member of the original paid-off crew of the Sand Merchant to get hired back on. Although he had a mate's certificate, he had been working as a wheelsman and now was happy to accept a job as crane operator.

First and second cooks Henry Lytle and Frank Burns, both from Toronto, had been working together for years. First mate Bernie Drinkwater was from Port Stanley, and the rest were from scattered communities along the lakes, from Thorold to Ft. William, Ontario.

En route to her Lake Erie assignment, the Sand Merchant took on a load of sand in Lake Ontario near Simcoe Island, delivered it to Toronto, and made a single trip from Niagara to Toronto, before Captain McLelland, now in his third year as a skipper, took his vessel through the Welland Canal and into Lake Erie.

The primary Lake Erie pumping grounds for the sand suckers was off the Canadian shore, between Southeast Shoal Light and Point Pelee, near the western basin of the lake.

Like the Charles Dick, the Sand Merchant was specially designed and built at the Collingwood Shipyards as a self-loader and unloader. Large port and starboard suction pipes were lowered into the sand banks on the bottom. Large centrifugal pumps sucked the sand aboard and propelled the mixture of sand and water along pipes or ducts on each side of the vessel, passing through screens and into the two hopper-like cargo holds. The excess water coming inboard was drained from the sand cargo by spillways provided for that purpose, through the vessel's sides. Water that escaped the spillways found its way to a sump in the after-ends of the hoppers and was discharged overboard by a special pump.

The Sand Merchant did not have hatch covers over the open cargo hoppers, this made possible by her unusual supplementary buoyancy features, four particularly large tanks fitted on either side of the cargo hoppers. These buoyancy reserves were in addition to her usual tank capacity. The ship was, in other words, designed to be a stable, seaworthy vessel, despite the temporary fluidity of her cargo, which quickly settled down into a dense, inert mass. The hatch or hopper coamings themselves extended thirty inches above the deck, and no amount of water coming aboard during stress of weather conditions should alter her stability to a significant degree. Topsides she was a rather strange-looking creation by virtue of the framework that supported her unloading boom and the continuous conveyor belt and buckets that dug out the cargo. Cranes forward, lowered, raised and maneuvered the long suction pipes. Baroque in appearance, the Sand Merchant was the epitome of efficiency, built to do a specific job with a minimum of blustering or complaining.

Once on Lake Erie she went about her workaday tasks with the ship, master, and crew evolving a methodical routine that varied little except for cargo destinations. The construction business being at a low ebb, the Sand Merchant wandered about a bit, sucking up sand east of Pelee Point and delivering her loads to Marysville and Port Huron, along the St. Clair River, and to Windsor, Cleveland, Toledo, and Lorain. When both hoppers were up to heir usual marks with cargo, the total burden was about 2200 cubic yards (2900 tons). When fully laden the ship slogged along at a sedate pace of about eight and one-half miles per hour .

At nine o'clock on the evening of Friday, October 16, 1936, shortly after unloading a cargo of sand at Windsor, Ontario, the Sand Merchant departed her dock for the five-and-one-half-hour trip back to the pumping grounds. Missing from the crew roster was boatswain John Hebert, of Rexton, New Brunswick, who had received permission to lay off for one trip. But the total complement of people aboard remained the same, since first mate Bernie Drinkwater had arranged for his wife, Lillian, to make a trip. The Sand Merchant's next cargo was to be delivered to Cleveland, after which another load was scheduled for Windsor, where Mrs. Drinkwater would depart. It was against the rules, of course, but the life of a sailor is a lonely one, and skippers were often wont to wink at official dictums.

At approximately 2:30 A.M. on the seventeenth, the Sand Merchant arrived at her designated working area. The large suction pipes were lowered and the process of taking aboard another cargo began. It was a clamorous operation, with the big pumps thundering and water and sand surging through the pipes, along with the clanging and other noises associated with a working vessel. It was a din that off-duty seamen learned to live with and ignore.

At two o'clock on Saturday afternoon, the hoppers having received their normal capacity, the suction pipes were raised and the Sand Merchant came around on the Cleveland course. The wind was blowing quite briskly from the northwest, lifting a modest sea and tearing the black smoke from the boat's funnel, driving it on ahead in fragmented streamers.

The vessel had been under way for less than an hour when her steering cable parted. Captain McLelland immediately ordered the port anchor dropped, and when the sand sucker had been brought around, head to wind and sea, the task of renewing the broken cable began. This required removing two oval manhole covers on the starboard side of the deck so men could enter the buoyancy tanks to pass the new cable through each bulkhead. Herman and Amos Dault were included in the repair gang, and when the job was completed, Herman personally supervised the bolting down of the manhole covers or scuppers. At six o'clock the anchor was hoisted and the voyage to Cleveland was resumed.

Tired, Captain McLelland had his dinner and then lay down to nap on a settee in the rear of the wheelhouse, instructing second mate Bourrie to call him when the vessel neared the Cleveland water intake "crib," five miles off the harbor entrance.

Meanwhile, the northwest wind had increased in force and sloppy following seas began boarding the Sand Merchant with some regularity. Captain McLelland was not a man who worried much about weather, although other shipmasters on Lake Erie that night were inclined to do so. Shortly after the steering cable repairs had been completed and the Sand Merchant put on her Cleveland course, two other vessels, the George L. Eaton and the Prescott, cleared Pelee Passage, eastbound. Their masters, not liking the looks of things, both hauled to port, taking the north shore route down Lake Erie, where both craft, each of which had much more freeboard than the Sand Merchant, would be in the lee of the land, in much calmer seas.

Two hours after he had put his head down for a nap Captain McLelland was awakened by the second mate, who advised him that the steamer had taken on a list to port. The list was not severe but seemed to be increasing steadily and for no apparent reason.

Captain McLelland did the only thing that made sense under the existing conditions, which included freshening winds and higher seas: he hauled the Sand Merchant around, checked down to half speed ahead, and took the wheel himself while his men sought out the reason for the list. In the half-ahead engine status, practically hove-to, he noted that the vessel was getting sluggish, a fact he later attributed to seas roaming over open hatches, carrying sand and water into the "wings" or open spaces under the deck, along the hoppers or holds. When his rudder manipulations and more speed on the engine failed to keep the Sand Merchant headed into the wind and seas, the vessel growing more sluggish with every passing moment, the good Captain McLelland concluded that foundering was not only a possibility, it was imminent. He had been called by the second mate at about nine o'clock and within a half hour the situation had become hopeless. In the assumption that through some mishap or mistake the large buoyancy tanks on the port side had been damaged and thus open to the sea, the crew had operated the associated pumps but got no water. If there was a leak, and obviously there was a catastrophic one, it was not in the buoyancy tank. Other compartments, the pump room, and machinery spaces were likewise clear of inrushing waters. Still, the list increased by the moment.

Shortly after he had been awakened Captain McLelland had ordered his mates, Drinkwater and Bourie, to prepare the lifeboats for launching. Bourrie secured the flares from the lifeboats and proceeded to fire them off. The ship's whistle began sounding the distress signal, and some of the crew augmented the flares by burning mattresses and bedding on the boat deck. It was a macabre situation and so incongruous - a vessel sinking literally within sight of the lights of Cleveland, displaying and sounding the age-old signals of distress for the better part of an hour and yet going down apparently without a soul ashore or afloat being aware of her plight.

When no help arrived in response to their flares and numerous mattresses set ablaze, the crew of the Sand Merchant could only conclude that their desperate signals went unobserved. As a matter of fact they were seen, but by people who did not interpret their meaning.

After three weeks of fruitless searching for the wreck, U.S. Corps of Engineers people made a survey of shoreline residents west of Cleveland, seeking citizens who may have sighted anything unusual on the lake the night of October seventeenth.

Bert Morrison, a compass adjuster, had already reported that on the night of the disaster, as he drove into the yard of his home, he had noticed a vessel's running lights. As he saw no distress signals at the time, he concluded that it was a ship swinging around at anchor or a fishing tug delayed in its work.

Still seeking witnesses, K. M. Harvey of the Corps of Engineers later talked to August Vian, who operated a barbecue restaurant just east of Lorain. He had not noticed any flares but had observed the fitful blazing of the mattresses, a sight he did not associate with a vessel in distress.

Another witness was Geraldine Kotz of Avon Lake. Returning home after a school meeting shortly before ten o'clock that fateful night, she watched some unusual light aboard a vessel. Since the rest of her family were already in bed, she made no mention of it until the next morning, when she remarked that someone on the boat must have been holding a Fourth of July celebration.

Later, by plotting Mrs. Kotz's estimated line of sight with those of August Vian and Bert Morrison, Captain Nimrod Long took the government steamer Peary to the triangular spot on the chart where the lines of sighting converged and there found the Sand Merchant, six miles north-northeast if Avon Point.

Although first mate Bernie Drinkwater aroused the off-duty hands and urged them topsides, he remained strangely missing from the boat deck, where his shipboard responsibilities required that he take charge of preparing and launching the lifeboats. Second mate Bourrie took over in the emergency. Mate Drinkwater was witnessed several times near the door of his room, on the starboard side, forward, apparently trying to calm his distraught wife.

It was an eerie scene there on the boat deck as crewmen tried to lower the boats. Only slight illuminations was provided by a couple of feeble light bulbs and the burning mattresses, which flared up occasionally and smoked villainously. Due to the pronounced list to port the starboard boat could not be launched, so the falls were slashed to permit it to float free when the steamer went down. The port boat was lowered even with the canting deck, and some of the crew climbed aboard while others operated the falls. Sometimes during the nightmarish scrambling in the dark, first mate Drinkwater must have come up on the boat deck, for when deck engineer Jack Meuse saw the port lifeboat being lowered, Lillian Drinkwater was aboard.

At this moment the Sand Merchant lurched sharply and then, as her coal bunkers shifted, rolled over, disappearing in a cloud of black smoke and steam and with a thunderous noise of conveyors, deck machinery, and unloading gear tearing free. The men had expected her to go soon, but not that suddenly. Captain McLelland, the only man left in the wheelhouse, simply dove free off the bridge wing. Aft, those on the boat deck were thrown clear as the sand sucker made her precipitous and fatal roll to port. The port lifeboat, still connected to the boat falls, flipped over but broke free. In the space of a few seconds the ship's full complement of crew was thrashing around in the darkness, yelling, cursing, and desperately seeking support. Both lifeboats surfaced upside down and immediately became havens of refuge for frightened sailors. Mrs. Drinkwater was not among those who gained the temporary security of either boat. Nor did her husband, mate Bernie Drinkwater.

Clawing and clutching but helping one another when they could, nine men found themselves trying to maintain a grip on one boat ... second cook Frank Burns, John Iderson, wheelsman Wilfred Bourrie, second mate Daniel Bourrie, Captain McLelland, fireman Ray Harper, and the brothers Dault-Amos, Joe, and Herman.

The second boat was a frigid haven for Jack Meuse, Harold Cannon, Peter Daigle, second engineer Martin White, William Gifford, and Fred Morse. Both lifeboats were swept repeatedly by the seas, washing the seamen off time and again. Gradually, as cold exhaustion took their toll, fewer were able to regain their tenuous holds on the keels and rope hand grips. Harold Cannon, Captain McLelland's fellow townsman from Cape Tormentine, was the first to go.

At approximately 8:30 the next morning, Sunday, October 18th, two vessel skippers, outbound from Cleveland, were somewhat startled to sight capsized lifeboats bobbing about in the morning slop, each supporting men who waved and shouted. The Marquette & Bessemer No. 1 maneuvered close to one lifeboat, threw ropes, and hauled in Jack Meuse, Martin White, Fred Morse, and William Gifford. Not far away, the Thunder Bay Quarries turned to provide a lee and picked up three men, all that were left from the nine that had clung so tenaciously to their lifeboat throughout the night. They were Captain McLelland, John Iderson, and Herman Dault. Joe Dault had slipped away even as the Thunder Bay Quarries turned from her course to effect the rescue.

On both rescue vessels the chilled survivors were hustled into dry clothing and provided with hot food and potent spirits. Their recovery was amazingly rapid. The Marquette & Bessemer No. 1 retraced her track and delivered the shipwrecked sailors she carried to a Cleveland dock. The Thunder Bay Quarries, en route to nearby Sandusky for a coal cargo, continued on to that port, where Captain McLelland and his two crewmen departed in good order.

Ten days later, in the Toronto office of Captain Henry King, Examiner of Masters and Mates, the preliminary inquiry into the foundering of the Sand Merchant brought some embarrassing moments and questions for Captain McLelland. There would have been even more embarrassing questions for first mate Drinkwater, but, alas, he was beyond this life.

Captain King, a kindly man, merely sought to determine if the master of the Sand Merchant had been conscientious in his handling of his vessel and his men.

Q. When you got underway after the transmission cable repairs had been completed, about six o'clock, what course were you on?

A. Sou'east by east.

Q. Was that magnetic or by compass?

A. Magnetic.

Q. Sou'east by east?

A. Yes.

Q. Are you sure of that? It was sou'east by east, by your compass?

A. Yes.

Q. Then your compass was out. But that of course had no bearing on your sinking.

A. No.

Q. Did you know the deviation of your compass?

A. The one in the wheelhouse ... you could not go very much by it.

Q. You had a standard compass?

A. Yes.

Q. And it was fairly reliable?

A. Yes.

Q. Did you ever have to have it adjusted?

A. No, I did not get it adjusted; not since I have been on her.

Q. Did you ever have a lifeboat drill on that ship?

A. No, not since I was on her.

Q. The men had not the faintest idea then, how to lower a boat?

A. (No audible answer.)

Q. Do you not think it would have been better if you had a drill once in a while, to let them know exactly where they ought to go, or what they ought to do in case of emergency?

A. (No audible answer.)

Q. And you saw no reason to expect that there was going to be any kind of weather which would bother you when you left Southeast Shoal, because it would have been the simplest thing in the world to have slipped over to the north shore, if you were expecting heavy weather, and anchored there?

A. Yes.

Q. You felt satisfied there was not going to be anything there to bother you; is that the idea?

A. That is the idea. I felt sure I could make the trip.

Q. It is too bad; it cost nineteen lives somewhere, and we must try and find out just what the reason was.

A. (No audible reply.)

Q. Now, as far as the barometer is concerned; what you saw of it gave you no inkling of any kind of bad weather?

A. No.

Q. 29:90 ..

A. The barometer which was in the wheelhouse runs about 27:00 all the time.

Q. That certainly was not right. If that was 27:00 the bottom would have fallen out of everything.

A. She had been that way all summer.

Q. They were not working?

A. No.

Q. They were out of order?

A. Yes.

Q. Both of them must have been out of order?

A. (No audible answer.)

In the full report of the subsequent three-day investigation of the disaster, Captain McLelland really did not fare too badly. He was exonerated from blame in the circumstances but open to censure for failing to have lifeboat drills aboard his vessel and for permitting an unauthorized person to be aboard. Mate Drinkwater, had he been present, would not have gotten off as easily. Mate Drinkwater and Bourrie, particularly Drinkwater, were charged with the responsibility for the heavy loss of life, Bourrie because he had been tardy in awakening Captain McLelland, and Drinkwater because he had completely failed in his assigned and traditional responsibilities as the ship's first officer.

In Superior Court in Toronto, the Honorable Mr. Justice Errol M. McDougall, wreck commissioner, assisted by Captain George D. Frewer and Mr. L. McMillan, nautical assessors, found that the Sand Merchant's foundering was due to the shifting of her cargo of sand, caused by the incursion of water through her open hoppers and possibly into her special buoyancy space.

The fact that the vessel should founder in circumstances she was specifically constructed to weather continued to puzzle the investigators, particularly after Captain McLelland testified that the Sand Merchant had several times actually loaded at the pumping grounds when the seas were mounting her deck. In their Annex to the Report, explaining their conclusions, the Court touched on the riddle several times. "Much anxious consideration has been given to the surprising phenomenon that this vessel should have gone down so suddenly. Her buoyancy space was so great and the capacity of her tanks so considerable that it is astounding to note that she should not have remained afloat for some time after she had turned on her side." The Court thoroughly explored the suggestion that the port buoyancy tanks may not have been quite dry and, through inadvertence or otherwise, may have been wholly or partially filled with water, but the evidence seems to negate any such conclusion. How then, could this vessel have disappeared so rapidly?

In the places where seamen gather to ponder the sinking ships and the loss of shipmates, it was apparent that something had gone amiss, whether by human error or mechanical failure. The Court could only surmise and hint as to such a conclusion, for the men who might otherwise have supplied the answers were forever gone.

Although official criticism was directed at others, and more specifically at her husband, there was no question in the opinion of the Court that Lillian Drinkwater's presence aboard the Sand Merchant was a contributing factor in the heavy toll of lives. The Court pointed out that no authority was obtained from the owners and that the "purely customary privilege" statement by Captain McLelland was no justification for her being a passenger. Said the Court,

"In the sequel this disregard of a rule, which is perhaps more honored in the breach, may have contributed and, in the opinion of the Court, did contribute materially to the appalling loss of life which occurred. Distracted by the presence of his wife aboard, the first officer, who is shown to have been a competent seaman, in the fact of imminent peril to all aboard, appears rather to have been more solicitous to his wife than to his obvious and paramount duty of getting the boats out and the crew aboard, as he had been directed by the master. How else can the almost total absence or mention of the first officer be explained? He was seen by one of the witnesses, some twenty minutes before the ship went down, standing at his cabin door with his wife. From that time forward, no member of the crew mentions him."

So there it was. A month after the ill-fated Sand Merchant found her eternal moorings, poor Lillian Drinkwater, who ventured from Port Stanley to be with her husband for one short trip, became, more or less, the cause celebre in the deaths of her husband and seventeen men she scarcely knew. Her presence aboard was an infraction of a rule or regulation, the violation of which had the tacit approval of many shipmasters. It was a governing principle that even the Court admitted was perhaps more honored in the breach.

Said to be "the last word" in ships of her class at the time.

The Sand Merchant's one surface condensing steam engine was supported by two scotch marine boilers, 13 feet in diameter, 11 feet long, with a working pressure of 200 pounds. Self loading and unloading, with cargo carried in two open hopper side holds. Sand and/or gravel was pumped into these holds by two 18-inch diameter centrifugal pumps, through large suction pipes lower into the sand banks on the bottom. It was also possible to screen gravel down to a desired size. The vessel was designed to be both stable and seaworthy, while accomplishing the task of loading and unloaded her cargo with minimal stress to the crew.

Cargo was unloaded with the assistance of two derricks with grab buckets, in addition to a continuous conveyor belt system. Four large tanks were fitted on either side of the cargo hoppers to aide in stability and buoyancy. Her normal working crew was composed of 26 individuals.

Operated to some extent during 1932, with no operations during 1933. 1934 through 1936 found her in service on both the Great Lakes and the Canadian East coast.

Ships and Men of the Great Lakes, Dwight Boyer, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York 1977. ISBN 0-396-07446-4 (pgs. 74-87)

The Great Lakes Diving Guide, Cris Kohl 2001, Seawolf Communications, Inc. P.O. Box 66, West Chicago, Illinois 60186 (416 pgs.)

Great Lakes Historical Society, Peachman Lake Erie Shipwreck Research Center (GLHS/PLESRC), P.O. Box 435, 480 Main Street, Vermilion, Ohio 44089 Historical Files and Photo Collections

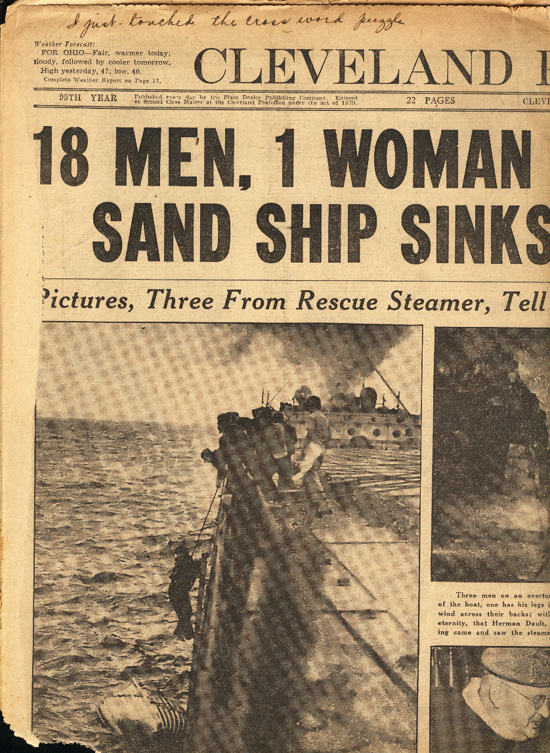

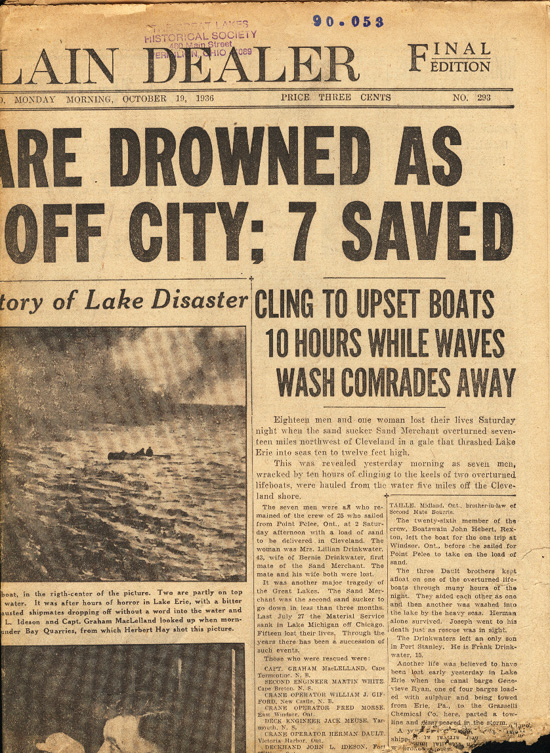

Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 19, 1936

Marine Review, October, 1927

Lorain Journal and Times Herald, October 19, 1936

MAST website and printed brochure

Institute of Great Lakes Research, BGSU