Cortland

| Ship Name: | Cortland |

|---|---|

| Also Known As: | Cortlandt |

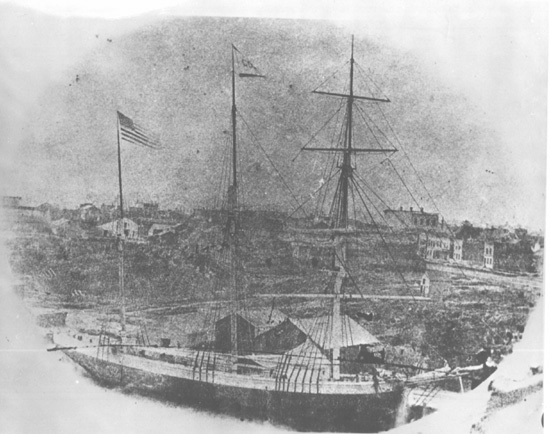

| Type of Ship: | Wooden Bark (barkentine), Three Mast, Bulk Freighter |

| Ship Size: | 174' length x 34' beam x 13'6" depth of hold |

| Ship Owner: | A.P. Lyman, Sheboygan, Wisconsin |

| Gross Tonnage: | 676 |

| Net Tonnage: | NA |

| Typical Cargo: | Bulk Freight |

| Year Built: | 1867 - A. Huntley, Sheboygan, Wisconsin |

| Official Wreck Number: | 5397 |

|---|---|

| Wreck Location: | Currently protected to preserve integrity of the wreck. |

| Type of Ship at Loss: | Same-not altered |

| Cargo on Ship at Loss: | Iron ore |

| Captain of Ship at Loss: | G.W. Lawton |

Prior to July, 2005, the Cortland was just another "Lake Erie Phantom Ship." The collision between the Morning Star and Cortland is one of the most noteworthy in Lake Erie maritime history, due primarily to the number of lives lost and the detailed accounts given by survivors. The incident was front page news for weeks, as bodies from both vessels continued to wash up on Lake Erie's shore. What makes it more interesting is that after many years of private and commercial divers searching for the wreck, she was found in 2005.

The Cortland was reported found on Saturday, July 30, 2005, by divers David VanZandt and Kevin Magee, founders of the Cleveland Underwater Explorers (CLUE). The bark has been said to have been one of the most sought after in Lake Erie.

The last time the Cortland's bell sounded was June 20, 1868, just prior to the collision.

On Tuesday, August 22, 2006, with the necessary permit from the State of Ohio, CLUE divers VanZandt and Magee, along with Carrie Sowden, archaeological director for the Great Lakes Historical Society's Peachman Shipwreck Center, Vermilion, Ohio, brought the Cortland's 100 pound bell to the surface from her final resting place 60 feet below.

*NOTE: Retrieval of artifacts from a shipwreck is a violation of Ohio's 1991 Shipwreck Protection Law without approval from and a permit issued by the State of Ohio.

The following site is a rather lengthy but exciting account from VanZandt and Magee of the dive during which the Cortland was located. This account was taken directly from the original email sent to Carrie Sowden, archeological director for the Great Lakes Historical Society's Peachman Shipwreck Center, Vermilion, Ohio, and dive members of CLUE, Lake Erie Wreck Divers (LEWD) and the Maritime Archeological Survey Team (MAST).

http://www.clueshipwrecks.org/Cortland.html

Saturday, June 20, 1868: Collision with the steamer Morning Star, approximately 16 miles north of what is now Lorain, Ohio. (See the Morning Star entry for more detail regarding the collision).

The Cortland was a 170-foot-long bark built by Mr. A. G. Huntley of Sheboygan, Wisconsin, in 1867 and was lost on the night of June 20, 1868, after a collision with the Morning Star, a side-paddlewheel ship carrying cargo and passengers from Cleveland to Detroit. The Morning Star sank very quickly and took many lives with her. The Cortland drifted about 3/4 mile southwest and sank an hour or two later.

The cause of the accident was never totally clear. One account indicates the Cortland's green navigation lantern had been taken down for cleaning by the first mate, leaving the Morning Star unable to see her. Ironically, the mate was returning the lantern to the rigging when the collision occurred, and he was killed when the Morning Star impacted the Cortland on the starboard side just behind the mizzen mast where the lantern was hung. Another newspaper (Chicago Tribune 6/24/1868) reported the captain of the Morning Star stating, "The bark had shown no lights, and although there was rain and fog, rang its bell only immediately before the crash."

The captain of the Cortland was reported to have answered this accusation by calling the Morning Star's captain a liar.

The Cortland was heavily salvaged soon after the sinking, and early divers reported she lay nearly on her side on a soft mud bottom in 12 fathoms (72 feet) of water. Despite early optimism, however, she was never raised. Prior to her sinking, the Cortland was less than a year old and built only two years after the end of the Civil War. No expense was spared when she was built, and she was one of the largest and best appointed sailing vessels on the Great Lakes at that time. It was also one of the earliest examples of the large sailing vessels that would come to dominate Great Lakes trade for the next decade.

There are many accounts of shipping and transportation disasters on the Great Lakes. The Detroit and Cleveland Navigation Company operated the Detroit/Cleveland run for over 100 years without a major incident until June 20, 1868. The following is a very interesting account of the Morning Star/Cortland disaster taken from Shipwrecks of the Lakes, by Dana Thomas Bowen, Chapter Seven, pgs. 51-57:

"These lines are being written in mid-May, 1951. Today at the foot of Third Avenue in Detroit and also at the foot of East Ninth Street in Cleveland are two very complete passenger terminal ticket offices and waiting rooms, heavily locked and barred. Spacious freight sheds and warehouses stand empty and bare. Shore dirt and grime are gathering. The stillness of the buildings is appalling. These are the offices and docks of the Detroit & Cleveland Navigation Company.

This year the company has suspended operation of all its five passenger steamers. For approximately a century, passenger ships have been operated between Cleveland and Detroit. Most of the runs were made overnight, though for many years a daylight trip was also made. Lake shore and riverside dwellers set their clocks by the passing of the trim side-wheelers. From the day that the ice permitted in the spring, until it froze over again in early winter, the D & C steamers moved across Lake Erie and up the Detroit River, carrying thousands of passengers and thousands of tons of freight on the one-hundred-and-eight-mile cruise.

The D & C steamers were a tradition. Today they await a somewhat dubious future. Time alone holds the answer. Many ships and many men have worn out together on this old time-honored route. It is the story similar to many other passenger steamer lines in North America. They are bowing out gracefully in favor of more expedient transportation mediums. One hundred years is a long time.

Whenever and wherever things move, there is risk. Every time a ship sailed, a potential danger prevailed. But the D & C line was remarkably free of trouble throughout all of its years of operation. This can be credited to many men: owners, shipbuilders, officers and crews, lighthouse keepers, government inspectors, and many others. Only one serious shipwreck resulted in the century of operation of passenger ships on the D & C route between Detroit and Cleveland. That occurred many years ago, on the dark and windy night of Saturday, June 20, 1868, almost eighty-three years ago.

Captain E.R. Viger commanded the side-wheel passenger steamer Morning Star on the Detroit-Cleveland run that year. The ship had been built but five years previously, entirely of wood as was the custom, and had made for herself an enviable reputation during that time. Captain Viger's record was equal in all respects to that of his vessel, except of course, for longer service. He had sailed the lakes since boyhood, and had risen from cabin boy to master by hard work.

It was exactly ten-thirty in the evening of that twentieth day of June, when Captain Viger piloted his steamer Morning Star out of the harbor of Cleveland on her regular run to Detroit. There were aboard forty-four first-class passengers and seven immigrants, in addition to a freight cargo consisting of one hundred tons of bar iron, several hundred kegs of nails, forty-five boxes of glass, twenty-five boxes of cheese, sixty-five tons of chill metal, thirty-three mowing machines, seven barrels of oil, four tons of stone, and one hundred thirty-seven kegs and boxes of various package freight.

Sailing vessels were numerous on the lakes in those days. In majestic silence they floated heavy cargoes of iron ore from the upper lakes to the ports on Lake Erie. One of these was the bark Courtlandt (sometimes spelled Cortland) with Captain G.W. Lawton in command. He had reached Lake Erie on his downbound voyage and had set his course for Cleveland, where his cargo of iron ore was consigned. Thus, the Courtlandt and the Morning Star were meeting on the same course.

The night was chilly, with a brisk wind out of the north, which whipped up a big sea along the course of both vessels. Captain Viger remained on the bridge of the Morning Star after they had cleared Cleveland; most of the passengers had retired. Several sailing vessels were sighted and passed, presumably headed for Cleveland. Midnight arrived and a dark night was noted on the log. Their position was off Black River, now the city of Lorain, Ohio. Just forty-five minutes later, while the passenger ship was proceeding at full speed ahead, she crashed into the bark Courtlandt with a terrific ripping of timbers, her bow piercing the hull of the wooden sailing ship about three-quarters the way back.

The only warning of impending danger that the officers of the Morning Star had was the ringing of the bell on the windjammer a few seconds before the crash. Then it was too late! They claimed that the bark carried no lights. Captain Lawton of the Courtlandt stoutly defended his situation by later stating, "I had just as good lights as ever were carried. I saw the steamer and kept on my course. I rang my bell three times and put my wheel hard up just before they struck."

The sharp prow of the steamer had cut almost through the bark. The force of the impact had torn the steamer's two bow anchors loose from their moorings, and hurled them forward. One of them slid entirely across the deck of the Courtlandt and into the water on the far side. The anchor chain then bound the two ships together, locked in a death struggle. Both vessels began to take in water fast.

Captain Viger called through his megaphone, "What vessel are you?"

"Bark Courtlandt with ore for Cleveland," came the reply, "We are sinking. Can you take our men aboard your ship?" asked the master of the sailing ship.

"We are sinking, too," replied Captain Viger.

The lights of one or two ships could be seen out over the lake, but their attention could not be attracted. In the rough seas the windjammer swung about and crashed broadside into the side of the steamer, smashing her paddle-wheel. The two ships were griding to pieces as the waves beat them together. It was futile to even attempt to save either craft, so every effort was bent on rescuing the passengers.

On board the Morning Star all was confusion, although the officers stood by their stations. Chief Engineer Watson was at his post in the engine room. He was thrown violently against his engine controls and rendered unconscious. He came to later and found himself struggling in the cold water, from which he was eventually rescued.

Captain Viger went to the main salon of his stricken steamer and tried to quiet his passengers by telling them that there was little danger. He sought the assistance of another lake captain whom he knew was on his passenger list, Captain Hackett of Detroit. The Morning Star's purser, James Morton, located him in his stateroom helping his wife into a life preserver and otherwise preparing for the worst.

Upon learning that Captain Viger needed his services, Captain Hackett asked the purser to continue to help Mrs. Hackett and he left for the steamer's bridge. Both Mrs. Hackett and Purser Morton lost their lives. Captain Hackett survived. The life boats, reported to be but two in number, were swung out and were quickly filled, mostly by the crew, although a few passengers managed to get into them before they were lowered away.

The Courtlandt managed to loosen herself from the Morning Star's anchor chains, and she drifted one half mile to the southwest before the waves rolled over her. Within a very few minutes both ships had sunk beneath the waves in seventy feet of water.

The hurricane deck was torn loose from the Morning Star as she sank, and it was the means of saving fourteen of the steamer's passengers and crew, Captain Viger included. Many perished as the last floating section of the steamer went down beneath their feet. Bits of wreckage floated about and covered the scene of the tragedy.

At three that morning the shivering survivors were heartened by the sighting of the lights of an oncoming passenger steamer. As it neared them they all shouted with all the human effort they could muster. They were sighted! The steamer began heading directly toward them and the mass of floating debris.

It was the R.N. Rice, sister ship of the Morning Star, making the opposite trip from Detroit, Captain William McKay in command. As quickly as possible, the crew of the R.N. Rice hauled out of the water the weary survivors of the ship collision. The officers and crew of the Courtlandt, with the exception of two, were rescued by the Rice. Captain Viger and his party clinging to the wreckage were also saved.

Another rescue was made that was a bit unusual. This was a lone man passenger who exhibited great calmness about the entire matter. Upon finding himself in the water he crawled onto a portion of deck that floated by. Soon a chair came within his reach. He dragged it onto his improvised raft and proceeded to sit on it. And lastly there drifted along a large metal cracker box, which he also brought aboard his temporary haven. When rescued he was sitting on the chair with his feet propped up on the cracker box.

The R.N. Rice continued her search for survivors until well after daybreak; then she headed for Cleveland, taking the rescued with her. She left behind her in the waters the dead, estimated from twenty-three to thirty-two. Many of the bodies were later located; others were never seen after the disaster.

But the business of lake passenger transportation was very vital in those days. The owners promptly replaced the ill-fated Morning Star with another fine side-wheeler, the Northwest, with Captain Viger as her commander."

NOTE - Among his many papers and documents of lake shipping, Mr. William A. McDonald of Detroit has in his possession an interesting signed statement of a survivor of the Courtlandt, the lookout, written after the tragedy. The paper states that just prior to the collision he had informed the mate that their starboard light was burning very dimly. The lamp was, of course, oil-fueled.

The schooner's mate then took down the light and cleaned off the accumulation of soot and trimmed the wick. He was in the act of replacing the cleaned lantern when the steamer Morning Star struck the Courtlandt. The mate was crushed in the collision and killed.

E-mail to C. Sowden from Kevin Magee, September 15, 2005

Great Lakes Historical Society, Peachman Lake Erie Shipwreck Research Center (GLHS/PLESRC), P.O. Box 435, 480 Main Street, Vermilion, Ohio 44089 Historical Files and Photo Collections

Shipwrecks of the Lakes, Dana Thomas Bowen, 1952, Lakeside Printing, Cleveland, Ohio "The Morning Star and the Courtland"

Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 1868

The Cleveland Leader, June 22, 23, 26, 1868

Lorain Constitutionalist, June 24, 1868

The Great Lakes Diving Guide, Cris Kohl 2001, Seawolf Communications, Inc. P.O. Box 66, West Chicago, Illinois 60186