Margaret Olwill

| Ship Name: | Margaret Olwill |

|---|---|

| Also Known As: | |

| Type of Ship: | Wooden Steamer |

| Ship Size: | 175.6 x 34.7 x 10.2 |

| Ship Owner: | L.P. and J.A. Smith Company, Cleveland, Ohio, Launched in 1887 |

| Gross Tonnage: | 554 |

| Net Tonnage: | 489 |

| Typical Cargo: | Stone/Limestone |

| Year Built: | 1887 |

| Official Wreck Number: | US 91953 |

|---|---|

| Wreck Location: | |

| Type of Ship at Loss: | Wooden Steamer |

| Cargo on Ship at Loss: | Limestone |

| Captain of Ship at Loss: | L.P. and J.A. Smith Company, Cleveland, Ohio, Launched in 1887 |

June 28, 1899

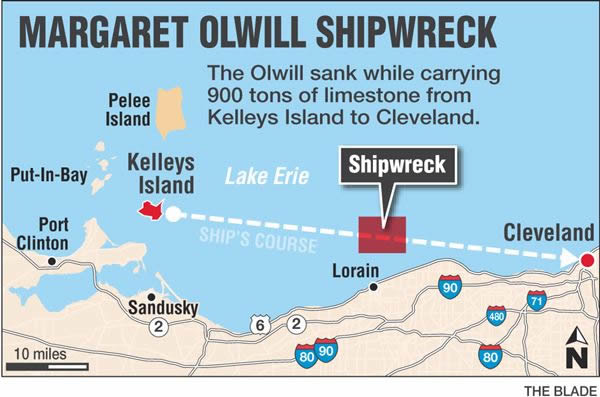

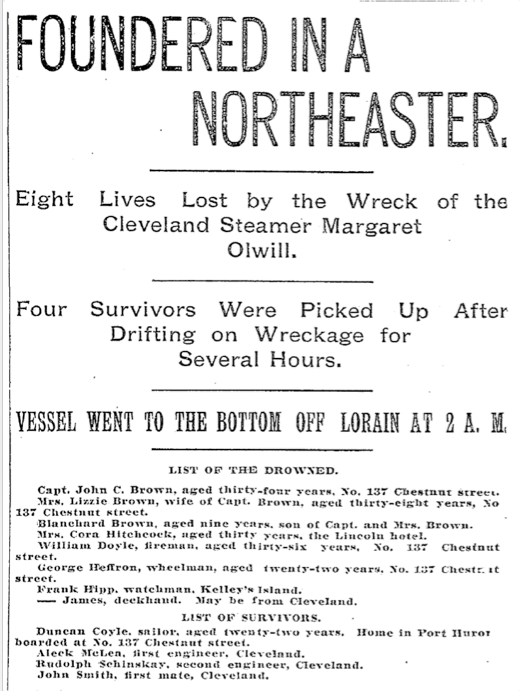

Margaret Olwill's last voyage took place June 28, 1899, in which it was carrying limestone weighing 900 tons. Among the 12 or 13 individuals on board the ship were Captain Brown's wife and young son Blanchard. A close personal friend of Mrs. Brown's, Cora Hitchcock Hunt, had been invited aboard for what had been invariably a routine excursion. Also invited were Captain Brown's parents, but his father declined after viewing the vessel. Missing this particular voyage was chief engineer Murphy, who had just been reassigned to another vessel owned by the Smiths over the protestations of both Brown and Murphy. With the hatch filled to the coaming, the ship could haul 300 tons. For this voyage, an additional 600 tons were placed on the deck. Although weather conditions were unfavorable and deteriorating, Captain Brown set course for Cleveland right at midnight. Soon after departure, conditions included winds of 50 miles per hour. Seams opened in the ship's hull, and Margaret Olwill took on water, which mixed with the limestone causing a significant list. Brown attempted to pilot the ship to shelter in Lorain, Ohio, but the steering chains failed at about 4:30 a.m., and the ship became broadside to the waves. With knowledge that the ship was certain to be wrecked, Brown ordered those aboard into lifeboats. Before his order could be carried out, a rogue wave swept over Margaret Olwill and capsized the ship, which soon sank at approximately 6 a.m. Before he was tossed overboard, Luke Schinski, had the presence of mind to grab a piece of canvass for assistance in rescue.

Four of the crew were rescued by the steamer State of Ohio and the steamer Sacramento, who found the men clinging to the boat's wreckage. Smith, McLea and Schinski had spotted the State of Ohio after several hours in the water, but the ship did not observe their wavings and hollerings, which greatly discouraged the men. However, the State of Ohio later found George Heffron and Duncan Coyle alive, clinging to a piece of the deckhouse amongst a large field of wreckage. The storm was still fierce, but ropes were thrown within reaching distance of both men. Coyle was able to tie the rope around his waist, but Heffron was too exhausted to grab onto the rope that was thrown to him, and slipped underwater as the State of Ohio's crew and passengers watched helplessly. The other group of three men renewed their frantic shoutings as they observed this rescue, but they remained yet undetected. Utterly discouraged, their hope was renewed when another ship was spotted by Shinski. This time they made the decision to coordinate their shouts, with the idea that the sound would carry further. This was successful, as the Sacramento gave a whistle and turned around to rescue the sailors. The Sacramento was a much larger vessel, and had considerable difficulty maneuvering with sufficient accuracy to rescue the men. Another vessel, the Cascade, noticed the unusual movements of the Sacramento and supposed the Sacramento to be encountering difficulty. Drawing alongside, the Cascade was able to pick up the two men that the Sacramento had been unable to reach.

Eight people died in the accident, including Captain Brown, his wife and son. The bodies of the deceased washed ashore east of Vermilion, Ohio. Much of the ship's wreckage beached at Cedar Point, Ohio and was sighted by John Brown's brother George Brown, who was captaining the steamer Arrow. Captain Brown has a reputation for following orders, thus historian Mark Thompson posits that Brown was obeying the ship's owners when he commenced the voyage, with ship overloaded and weather adverse. A contemporaneous insurance review supposed that Captain Brown, with long experience on Lake Erie, would not believe a small storm would become a major gale in June.

List of crew and passengers:

John C. Brown (Captain)- perished

Captain Brown's wife (passenger)- perished

Blanchard Brown (passenger)- perished

Duncan Coyle (seaman)- rescued by State of Ohio

William Doyle (fireman)- perished

George Heffron (wheelsman)- perished

Frank Hipp (seaman)- perished

Cora A. Hitchcock Hunt (passenger)- perished

Alexander McLea (chief engineer)- rescued by Sacramento

Luke Schinski (also spelled Cynski) (second engineer)- rescued by Sacramento

John Smith (seaman)- rescued by Sacramento

"James" (seaman)- perished

Possibly unknown (seaman)-perished

Shipwreck Discovery Report

Amazing New Discoveries!

February 15, 2018

Introduction

The process of locating and identifying shipwrecks is a time consuming one. Often it can take years from the initial discovery of a potential underwater target, to confirmation that the target in question is a shipwreck, to identifying a particular shipwreck as a specific named boat that was lost. Not only must time be spent on the water employing sophisticated technology, but significant time must also be spent on investigating primary source material as part of the confirmation process. Also, on Lake Erie, underwater photography of shipwrecks is unfortunately, difficult to undertake. Lake Erie is considered the murkiest of all the lakes and shipwrecks, particularly in shallow waters, are viewed with often less than four feet of visibility. By agreement, CLUE and The National Museum of the Great Lakes do not release the exact location of shipwrecks until such a time that the vessel can be formally surveyed in order to protect the submerged cultural site.

Recent Discoveries

Lake Erie continues to give up her long held secrets about early 1800 – 1900 shipping and sailing. Over the past several years the Cleveland Underwater Explorers (CLUE) have discovered three more shipwrecks and confirmed the identity of one. These discoveries continue to add to Ohio’s rich maritime history.

On July 17, 2016, CLUE members David VanZandt and Ken Marshall discovered a shipwreck while conducting sidescan sonar searches in the area where two other schooners are believed to be located. A highly broken up target was discovered but could not be investigated due to rough sea conditions. CLUE returned with a dive team on August 7, 2016. The target was investigated in poor visibility and was determined to be a sailing vessel, broken up and partially buried in the sandy bottom, in about 50 feet of water. It has been dubbed “Ken’s Tiller Wreck” until it can be positively identified. A sidescan image of the wreck appears in Figure 1.

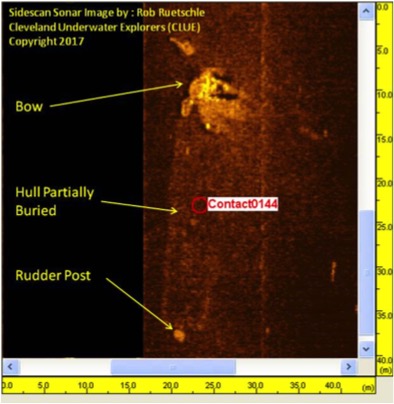

A few days later on July 22, 2016, another new shipwreck was discovered by CLUE member Rob Ruetschle (Figure 2). The wreck was dived on October 8, 2016 with the visibility being less than 1 foot. The wreck appears to be an old schooner with the bow, Sampson post, and windlass exposed, amidships is silt covered, and at the stern a rudder post protrudes out of the silt. The majority of the wreck is covered by about a foot of mud and silt. Two anchors are located off the wreck with one approximately 30 feet off the starboard bow and the other about 100 feet off the center bow. From the sonar images the bow is pointed, and the stern is square with a large object protruding out of the silted bottom about three to five feet off the stern. The length of the wreck is between 55 - 70 feet long determined from sidescan sonar measurements. The wreck had fish nets wrapped around the windless, some of which were cut loose and removed for diver safety. A small amount of coal was found on deck aft of the windlass possibly indicating the ship’s cargo. Future work also needs to be done at this site to obtain more data for a possible identification.

Figure 1 Sidescan of “Ken’s Tiller Wreck” (Sidescan by David VanZandt)

Figure 2 Sidescan of New Shipwreck July 2016 (Sidescan by Rob Ruetschle)

Propeller Margaret Olwill Found and Identified

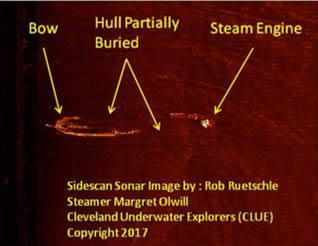

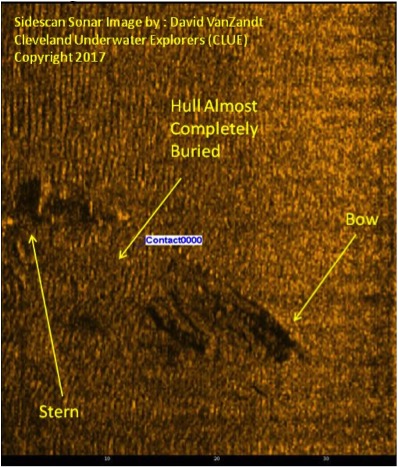

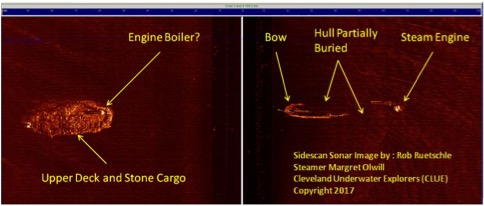

On July 26, 2017 CLUE member Rob Ruetschle discovered a shipwreck tentatively identified as the long sought after Propeller Margaret Olwill was lost in June, 1899. Rob had been searching for the Olwill for 29 years while CLUE had been searching for the Olwill on and off for 11 years. The tentative identification was based on the wreck’s location and the condition of the wreck compared to survivor accounts of the sinking (Figure 3).

Rob and Rudy Ruetschle began searching for this wreck in 1989, 21 years before Rob joined CLUE. Late in the fall of 1989 after finding a promising target in the original search area, they moved onto other wrecks thinking they would come back to this target to verify the identity of the wreck the next spring. They didn’t return to that site until late October 2016. Sidescan sonar images of the target identified a rock formation with a large, approximately four-foot diameter by thirty-foot-long, sunken log lying on top of the rocks all surrounded by a mud bottom. Not the elusive Olwill.

During December of 2016 Rob reexamined the old search area scans and all archival documents accumulated prior to the first search. After careful review he decided to take one more shot at finding this elusive wreck. He moved the search area and covered a new 25 square mile area before finding the wreck in the early evening of July 26, 2017. In all about 60 square miles of Lake Erie was searched to find this ship.

Rob dived the wreck for the first time that same evening. The wreckage consists of a stem which rises about 14 feet off the bottom. Aft of this is a steel windlass followed by bollards on each side. Two anchor chains run through hawser pipes on top of a deck block and run out and disappear into the mud on both the port and starboard sides. The port rail is up and has part of the deck house framing posts, 4 in total, still sitting about six feet above the rail. Aft of the deck house framing the rail runs about another 90 feet towards the stern before breaking and becoming buried in the mud. The wreck is listing to the starboard side where it becomes buried in the mud bottom which is pushed up several feet from the hard impact when it sank 118 years ago. The engine and boiler were not found on this dive, so a second dive was needed to confirm the identity of the wreck.

The following month a dive team consisting of Rob Ruetschle, Tom Kowalczk, and David VanZandt assembled and returned to the wreck site on August 9, 2017 to conduct a preliminary archaeological survey of the site. Dive conditions were marginal with an estimated visibility of 2 feet. The main objective was to document diagnostic evidence to support the theory that the wreck discovered was indeed the Propeller Margaret Olwill. That evidence was found early in the dive with the discovery of a vertical steeple steam engine located in the stern of the vessel. The steam engines layout is of a steeple configuration with a piston size of 36 inches. This matches exactly the historical data for the vessel’s machinery. So after 29 long years of searching by Rob and 11 years by CLUE we are confident enough in the evidence to announce the discovery of the shipwreck identified as the Propeller Margaret Olwill.

Figure 3 Sidescan Image of the Margaret Olwill (Sidescan by Rob Ruetschle)

History of the Ship:

OLWILL, MARGARET (1887, Steambarge)

Year of Build: 1887

Official Number: 91953

CONSTRUCTION AND OWNERSHIP

Built at: Cleveland, OH

Vessel Type: Steambarge

Hull Materials: Wood

Number of Decks: 1

Builder Name: Henry D. Root

Original Owner and Location: L.P & J.A. Smith, Cleveland

Power: Sail

Number of Masts: 3

Propulsion: Screw

Engine Type: Steeple Compound

# Cylinders: 2

# Boilers: 1

# Propellers: 1

Propulsion Notes:

20", 36" x 24" engine, 400hp, 104rpm by Cuyahoga Iron Works, Cleveland, 1870

7.5' x 16' firebox boiler, 90 pounds steam, by Smith & Teach or Cuyahoga Iron Works, Cleveland, 1881

DIMENSIONS

Length: 175.6'

Beam: 35'

Depth: 10.2'

Tonnage (gross): 541

Tonnage (net): 493

FINAL DISPOSITION

Date: 28 Jun 1899

How: Foundered

Final Cargo: 900 tons limestone

Notes: 8 or 9 of crew of 13 lost

HISTORY

1890 Rebuilt as propeller, 2 decks, 3 masts, 177.3' x 34.7' x 17', 925.33 gross tons

1892, July 18 Broke her shaft & leaking above Whitefish Point, Lake Superior, towed to Cleveland

1893 Rebuilt as steambarge, 1 deck, 3 masts, 175.6' x 34.7' x 10.2', 554.94 tons

1894, September 4 Ashore in smoke on Sand Island, Lake Superior; Released

1899, June 28 Foundered, Lake Erie

1899, September 26 Enrollment surrendered, Cleveland, Ohio

(Data from the Pat Labadie Database)

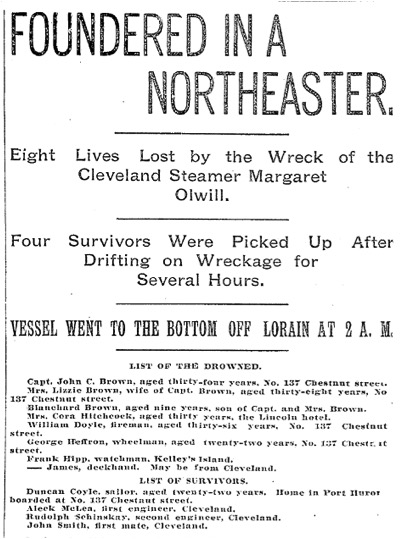

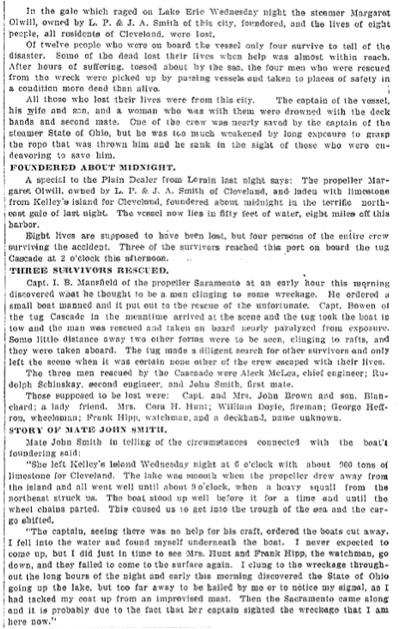

Description of Wrecking Event, Plain Dealer 30 June 1899, Page 1, Col 6:

Biographies:

David VanZandt, Director and Chief Archaeologist

David is the Senior Principal Engineer for ZIN Technologies, Inc., specializing in space flight hardware for NASA Glenn Research Center and has more than twenty years of experience designing, building, testing, and operating fluids and combustion experiments on the Space Shuttle, sounding rockets, and International Space Station. He began his diving career in 1995 and currently holds dive certifications up through trimix and AIMA/NAS Level 3. David began searching for and finding shipwrecks off his boat Sea Dragon in 2001 when he founded the Cleveland Underwater Explorers (CLUE). David graduated Purdue University in 1981 with a Bachelor of Science in Nuclear Engineering. He is also a graduate of Flinders University and holds several archaeology degrees including a Masters of Maritime Archaeology. David is on the Register of Professional Archaeologists (RPA) and is a member of the Ohio Archaeological Council (OAC), the Association of Great Lakes Maritime History (AGLMH), the Great Lakes Historical Society (GLHS), and the Society for Historical Archaeology (SHA). He is also a fellow in The Explorers Club.

Tom Kowalczk, Director of Remote Sensing

Tom is currently retired and an avid shipwreck hunter off his boat Dragonfly. He is a lifelong resident of Ottawa county Ohio and grew up fishing and diving in Lake Erie. Tom began diving shipwrecks in 1965 and has been researching Great Lakes history ever since. He holds an International certification of safe scuba diving from NASDS and is a past scuba diving instructor. Active in the Great Lakes community, he is a past board member of The Association of Great Lakes Maritime History (AGLMH), a member of the Great Lakes Historical Society (GLHS), and Save Ontario’s Shipwrecks (SOS). Tom is an experienced researcher, side scan sonar operator, and scuba diver.

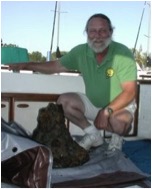

Rob Ruetschle, Research, Remote Sensing, and Diver

Rob is currently the CEO of Visiting Angels Malibu, CA. He holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Biochemistry and worked exclusively in the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing field for 25 years before becoming involved with Visiting Angels. Rob was raised around the water in the Great Lakes area where he learned to fish, water ski, and scuba dive in the Great Lakes with his family, who all are certified divers, and have been diving since early 1970’s. Soon after that he and his father became extremely interested in the history of the Great Lakes and began researching shipwrecks through the public libraries and museums around the Great Lakes. After locating several shipwrecks, they teamed up with Jim Paskert and Bob Tindal and became fully engaged in researching, locating, and documenting shipwrecks. Rob is an experienced researcher, side scan sonar operator, and scuba diver. He currently searches for and documents shipwrecks from his 32 foot Marinette Grand Sportsman, Scavenger.

Ken Marshall, Technical Diver and Surveyor

Ken is a Senior Consulting Engineer for Engineering Design & Testing Corp., specializing in forensic engineering conducting root cause investigations and damage analysis. He has over 25 ye ars of experience in the design, fabrication, assembly, operation, and maintenance of custom industrial equipment. Ken graduated from the University of Cincinnati in 1985 with a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering. He also earned a Master in Business Administration from Cleveland State University. Ken is a licensed Professional Engineer (P.E.) in 13 states. Ken began his diving career in 1979 and has obtained the rating of O/W Instructor. In addition he holds certifications in numerous specialties including gas blending, tri-mix, SCR rebreather, and cave. Ken’s interest in shipwrecks expanded in 1999 after taking the GLHS/MAST Nautical Archaeology for Divers Workshop, eventually earning his Underwater Archaeology Instructor certification. Ken is a past chair of the MAST Board of Directors and was the driving force behind the MAST shipwreck buoy program, that provides dive boat moorings for the protection of shipwrecks in Lake Erie's central basin, which he ongoingly manages. Ken continues as a member of the Great Lakes Historical Society (GLHS) and the Maritime Archaeological Survey Team (MAST).

- Van der Linden, Peter J. (1986). Great Lakes Ships We Remember. Cleveland, Ohio: Freshwater Press. P. 316.

- Boyer, Dwight (1977). Ships and Men of the Great lakes. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. pp. 14-29

- John Brandt Mansfield, ed. (1899). History of the Great Lakes: Volume 2- Biographical. Chicago: J.H Beers & Company. p. 949.

- John Brandt Mansfield, ed. (1899). History of the Great Lakes: Volume 2- Biographical. Chicago: J.H Beers & Company. p. 208.

- Johnson, Laura (March 15, 2018). New Shipwreck of Margaret Olwill discovered in Lake Erie. Rock the Lake. Cleveland Lakefront Collaborative. Retrieved March 27, 2019. https://www.cleveland.com/metro/2018/03/shipwreck_of_margaret_olwill_d.html

- John Brandt Mansfield, ed. (1899). History of the Great Lakes: Volume 2- Biographical. Chicago: J.H Beers & Company. p. 383.

- Thompson, Mark L. (2004). Graveyard of the Lakes. Wayne State University Press. P. 354.

- Lewis, Walter. Margaret Olwill (Propeller) sunk 28 June 1899. Maritime History of the Great Lakes. Retrieved March 27, 2019. http://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/61495/data

- Patch, David (March 15, 2018). Long-Sought Ship that Sank More than 100 Years Ago Found in Lake Erie. The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. Retrieved March 27, 2019. https://www.toledoblade.com/State/2018/03/15/Ship-that-sank-more-than-100-years-ago-found-in-Lake-Erie.html

- Steer, Jen (March 16, 2018). Lake Erie Shipwreck Identified as Steam Barge that Sank off Lorain in 1899. Fox 8 Cleveland. Retrieved March 27, 2019. https://fox8.com/2018/03/16/lake-erie-shipwreck-identified-as-steam-barge-that-sank-off-of-lorain-in-1899/

- Nine Lost in Lake Erie. New York Times. June 30, 1899. p.1. Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- Cleveland Underwater Explorers, Inc. website available at: www.clueshipwrecks.org

- Margaret Olwill. Wikipedia. Retrieved March 27, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Olwill